Projects

We study natural populations using a combination of field-work, genomics, and common-garden experiments.

Featured

Molecular mechanisms of dwarfism and organ allometry in Atlantic salmon

Species radiations can be driven by changes in body proportions (allometric changes), that is, natural selection acting on size and not in shape. Discovering the genetic and developmental basis of allometry has both fundamental importance for understanding the emergence of biological diversity, as well as in practical terms such as in understanding cancers. Only a few allometry mechanisms are known to explain adaptive differences in organ size within a vertebrate species. Salmon show a fascinating adaptation of organ allometry associated with a trade-off in life history strategies; dwarf landlocked ecotypes prioritize egg size over egg number, and in consequence have ovaries that are 50% smaller compared to their sea-migrating congeners. The decreased ovary size in dwarf salmon provides a unique model to study how allometry emerges within a single species and interplays with life history strategy. Our work in collaboration with Prof Dylan Fraser at Concordia University is dissecting the genotype-phenotype-fitness map of ovary allometry from the molecular to the species level with an integrative approach combining cellular genomics, gene editing, and a powerful quantitative genetics framework.

Molecular mechanisms of maturity age variation in Atlantic salmon

Trade-offs between life history traits such as growth and reproduction are common in nature. One example of such is seen in Atlantic salmon where prolonged sea-migration translates to larger size at maturity, and therefore higher fecundity, but with the cost of increased risk of dying before reproducing. The genetic basis of maturity age has been associated with two major effect genes, vgll3 and six6 (Barson, Aykanat et al. Nature 2015), plus hundreds of smaller effect loci. Despite explaining a large proportion of variation in maturity age, the mechanisms translating genetic differences in these genes into different life histories are largely unknown. In collaboration with Prof Craig Primmer at the University of Helsinki, we study the molecular mechanisms that translate vgll3 and six6 genotype variation into differences in maturity age. Our results so far indicate that vgll3 controls the activity of thousands of other genes that each determine different aspects of pubertal onset (Verta et al. PNAS 2024). Our research explain how single genes can mediate variation in traits as complex as life histories - even though the genetic basis may be simple, the functional mechanism connecting it to life histories can be very complex. Photo by Mikko Ellmen.

More

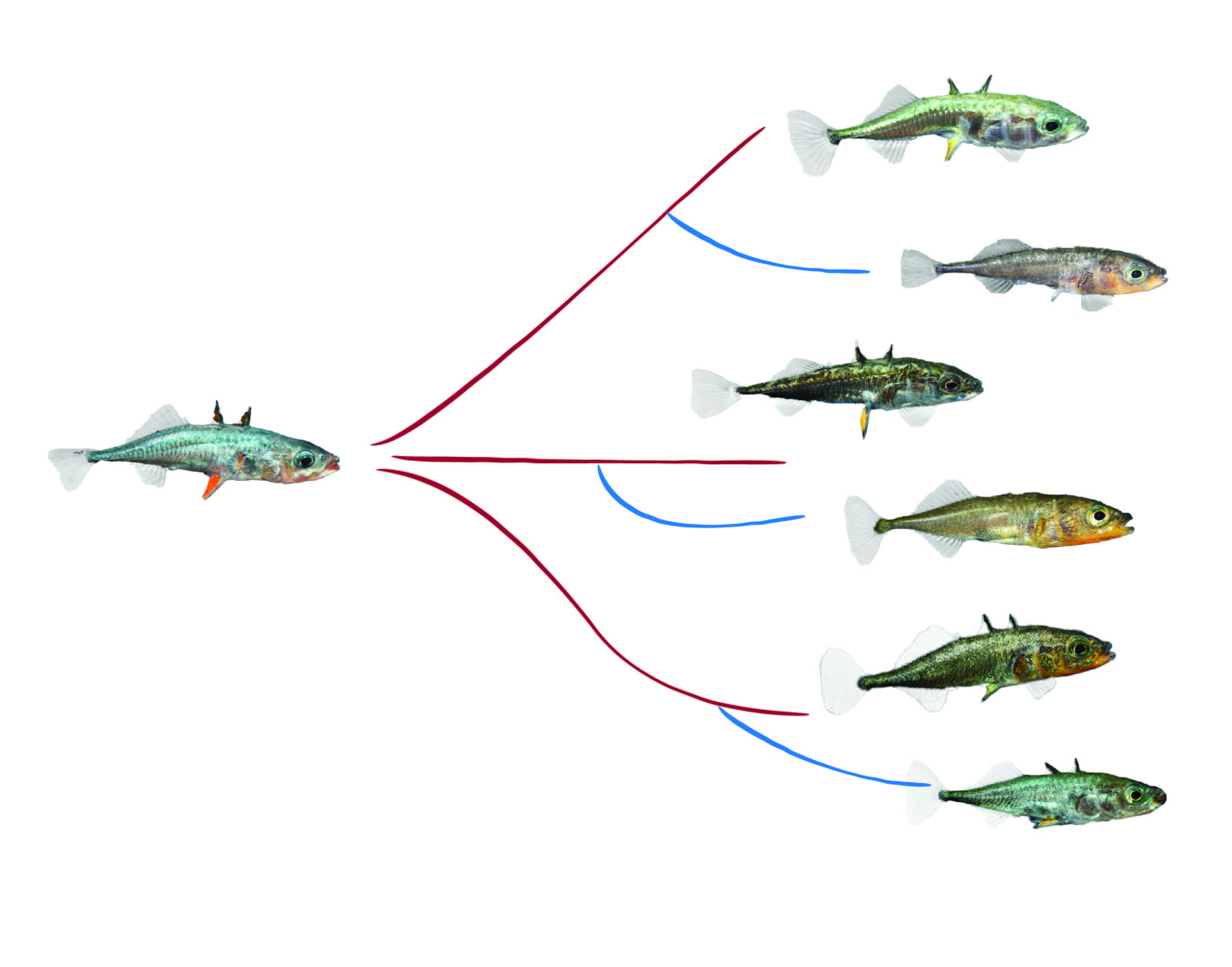

Genetic basis of gene expression divergence in threespine sticklebacks

Variation in gene regulatory mechanisms play an important role in producing phenotypic variation that natural selection can act upon. Regulatory evolution seems to be tightly linked to both adaptive divergence of lineages as well as divergence of established species. We have a poor understanding of regulatory evolution during the very early stages of incipient speciation where adaptation-with-gene-flow still dominates, as it does in sticklebacks. These fish are a great model to study regulatory evolution at short divergence timescales as many of the freshwater environments sticklebacks have colonised were formed after the last glaciation only ~10 000 years ago, and the repeated nature of freshwater adaptation provides a system where we can study regulatory changes that have occurred in parallel in independent bouts of adaptation. In collaboration with Prof Felicity Jones at the Max Planck Institute Tübingen, we characterised gene regulatory divergence between freshwater and marine sticklebacks in order to better understand the contribution of different regulatory mechanisms to adaptation and incipient speciation (Verta & Jones eLife 2019). To reach this goal we used whole-genome and mRNA sequencing combined with bioinformatics and statistical analyses to explore the ways in which gene expression divergence in the gill tissue is linked parallel freshwater adaptation.